Rebate-based text scams are circulating widely again, and they are strategically crafted and geo-targeted to follow current local trends. The premise is simple and tempting: unexpected money is waiting, and all you need to do is verify a few details. Scammers know that inflation, holiday spending, rising fuel costs, and even grocery pricing have made people more receptive to financial relief claims. That psychological leverage is what makes this scam so effective.

Rebate-based text scams are circulating widely again, and they are strategically crafted and geo-targeted to follow current local trends. The premise is simple and tempting: unexpected money is waiting, and all you need to do is verify a few details. Scammers know that inflation, holiday spending, rising fuel costs, and even grocery pricing have made people more receptive to financial relief claims. That psychological leverage is what makes this scam so effective.

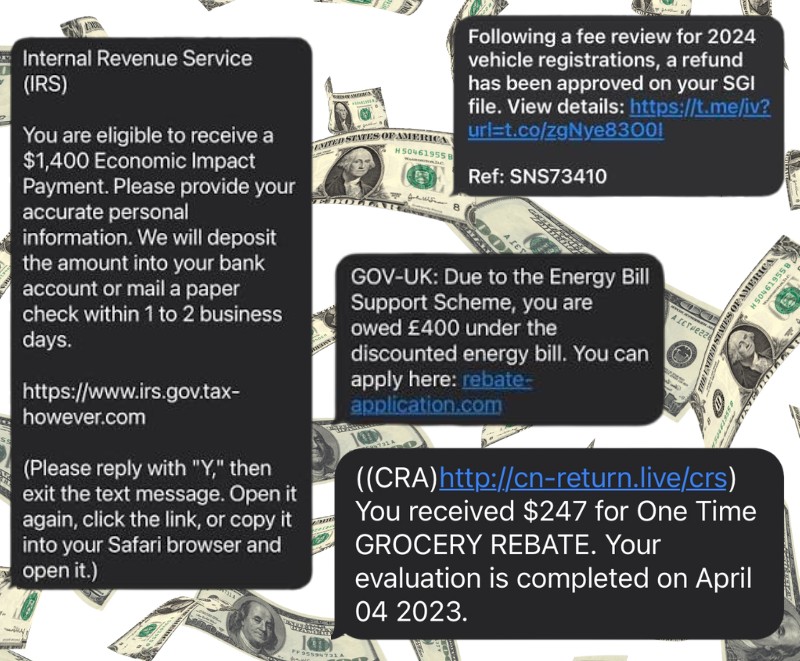

What victims often see first is an abrupt message referring to a refund or credit already approved in their name. Some versions reference vehicle registration adjustments. One current message reads,

“Following a fee review for 2024 vehicle registrations, a refund has been approved on your SGI file.”

The link attached leads to a counterfeit portal designed to collect banking information. Others impersonate national tax agencies, sometimes copying wording borrowed from legitimate COVID-era relief programs. For instance, a recent example claimed that recipients were still eligible for a $1,400 stimulus payment, urging them to confirm their identity so that the deposit could be released.

None of these communications originate from official government channels. Financial institutions and tax agencies do not push refunds by text and do not condition payment on immediate link clicks. What these messages actually achieve is identity harvesting. Victims are redirected to a fabricated website and asked to enter banking credentials, addresses, Social Insurance or Social Security numbers, or credit card information. Once supplied, it is either sold, used to initiate account access attempts, or retained so fraudulent benefit claims can be filed under the victim’s identity.

Some versions attempt to contextualize themselves within real-world economic news. When the cost-of-living conversation intensified in various countries, scammers began sending messages referring to grocery aid programs. One circulating example states,

“You received $247 for One Time GROCERY REBATE. Your evaluation is completed.”

While it appears believable, the date referenced did not align with any government program, which is how many recipients realized something was wrong.

Energy subsidy variations follow the same pattern. When utilities increased billing estimates, a wave of messages claiming households are owed hundreds toward energy support programs. A prominent example referenced a well-known UK-based energy scheme, offering £400 and directing recipients to an application portal that imitated a legitimate rebate webpage. Its layout and colors mirrored the genuine government format, which is often enough to override skepticism.

A consistent red flag is the style of the link. Scammers attach domains ending in .live, .xyz, .top, or altered spellings resembling tax agencies or regulatory sites. Links such as cn-return.live/crs or irs.gov.tax-however.com are designed to look authoritative while bypassing basic recognition filters. Some instructions also attempt to defeat spam blocking by telling recipients to reply with a letter, reopen the message, or copy-paste the link into a browser manually.

Once the victim interacts, losses rarely occur immediately. The data gathered is often used days later, sometimes weeks, after being combined with additional information purchased from separate breaches. That delayed effect is why most victims do not connect the event to the original message.

When Clicking the Link Becomes a Malware Trap

One overlooked danger in rebate text scams is how not all fraudulent links lead to imitation login pages. Some of them immediately trigger malware downloads. These attacks rely on automatic redirects, disguised security prompts, or downloads appearing as legitimate document files. Victims have reported landing on pages requesting “verification plug-ins,” claim a browser update is needed, or initiate a file download without warning.

In cases where malware is installed, the damage goes beyond stolen credentials entered manually. Certain strains are capable of capturing keystrokes, accessing stored passwords, or monitoring login activity in real time. Others install invisible pop-ups requesting banking verification weeks later, giving the impression the request is legitimate and unrelated to the earlier scam.

Malware-based versions are especially dangerous because victims do not always realize anything has happened. Even those who close the page immediately may already have background software running, silently transmitting data back to the scammer.

Anyone receiving such messages should avoid clicking links entirely and verify the claim directly through established portals. When available, suspicious texts can be forwarded to spam reporting services such as 7726, which helps carriers block cloned numbers. Individuals who entered personal data should immediately change passwords, notify their financial institution, and consider placing a watch or fraud alert on their credit file.

Rebate scams persist because they use hope as bait. When times are financially tight, messages offering instant relief appear harmless enough to open. Yet behind them sits a well-structured system designed to strip victims of far more than the small rebate they believed they were collecting. Awareness remains the strongest barrier, and skepticism is the protection scammers hope you will ignore.

- Log in to post comments